More is different

For my PhD research I study what happens when water molecules get together.

There is a difference between studying water and studying water molecules. One can study how water flows without ever considering that it is made of zillions of tiny molecules – that is the subject of fluid dynamics. One can also study how water flows and interacts with the environment – that study is called hydrology.

The subject I study is called molecular dynamics and it has to do with understanding what water molecules are actually doing on the microscopic level.

When I tell people I study water I sometimes get a puzzling look. People ask, “isn’t water pretty well understood?”. The popular perception of physicists (as covered in popular science shows) is that they are the people who study the more far flung aspects of the universe, such as dark matter, wormholes, and quantum entanglement. Why would a physicist want to study something banal as water?

There are several reasons I study water. For one thing, I actually like studying things which are commonplace and that I can observe in everyday life. For me, it is exciting and gratifying to have a deeper appreciation of the world that I see around me — “my own sensory world”. I guess this is a bit self-centered – most of the universe being outside the limited sphere of my senses — but then again I don’t have to worry about the rest of the universe getting jealous that I’m not interested in it, right?

Water is the medium of life – the staging ground of biology. The earth’s surface is 71% water and our bodies are around 57% water. Man has been able to bring water under a high degree of control — a vast infrastructure insures that we get an adequate supply of clean water for drinking, cooking and washing — an infrastructure so reliable that we rarely even consider it.

Water is so commonplace that the ancient Greeks considered it one of the five classical elements — to them it was one of the most simple things in the universe.

Since water is so important to us and so abundant in our environment, it has been heavily studied and its properties are extremely well understood. It is quite fair to say that no other substance has ever been so highly studied or had its properties so thoroughly cataloged. However, the more we learn about the properties of water, the more clear it is how much we really don’t understand where those properties come from and why they are so different than other substances. (There are still a few open questions about the fundamental properties of water – such as the vaguely posed “water structure problem” which has been dragged around for over a hundred years, and the question of whether water contains a second second-order critical point in its phase diagram, between the high density and low density amorphous phases. )

Water exhibits a large number of anomalies — properties that fly in the face of the way we normally expect liquids to behave and require special explanation. Martin Chaplin identifies 69 on these on his website — the chief among these being an anomalously high melting and boiling points relative to water’s small molecular weight, water’s expansion of volume upon freezing, and the lowering of the freezing point with pressure (so called “pressure melting”).

There are also a large number of “response function” anomalies, such as :

- The isothermal compressibility K_T has a minimum at 46 C and then increases at lower temperatures. (Usually K_T decreases monotonically with decreasing temperature.)

- The specific heat C_P has a minimum at 36 C and increases at lower temperatures. (Usually C_P decreases monotonically with decreasing temperature.)

- The thermal conductivity of water is unusually high and increases with temperature until reaching a maximum at 130 C. (Usually thermal conductivity decreases monotonically with increasing temperature)

Almost all the liquid water anomalies are related to the fact that water is the only substance with a low molecular weight which has a high density of hydrogen bonding — on average each water molecule has 3 – 3.5 hydrogen bonds at room temperature.

So far I hope to have to convince you that water is special. However, in this post I would like to discuss something not unique to water, but something which is is present almost everywhere in the universe — and that is the fact that more is different. The phrase “more is different” comes from a 1972 article in Science by Dr. Phil Anderson , which I highly recommend.

The idea of more being different is the same as the idea that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. This can be illustrated with almost any system in nature which consists of more than a few “parts” (be them atoms, molecules, cells, people or stars – in each case the more always proves to be new and more exciting). Here I will illustrate with water, because I believe it presents a particularly striking example.

The water molecule itself is pretty well understood. From a classical perspective the isolated water molecule is a rather simple thing — it’s easy to model as three charges connected by springs. Indeed, most of the models used in biophysics simulations are either “ball and stick” or “ball and spring” models. No ball and spring model can fully explain water, but they can do a pretty good job at relatively low computational cost. For instance, the hydrogen bond can be understood to be 90% classical electrostatics plus a Leonard Jones potential (this potential has its physical origin in quantum dispersion forces, but it’s treated according to classical mechanics, so its considered a classical potential). In general, it seems that purely quantum effects have about a 5-10% role in determining water’s properties and dynamics — a large number for something at room temperature, but negligible for many purposes.

If we bathe our water molecule with electromagnetic radiation (in particular, microwaves) it will vibrate in three different ways, known as modes, and will emit and absorb radiation. However there are few other interesting things that a single water molecule can do.

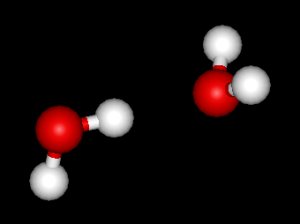

What happens if we bring two water molecules together? If they are allowed to relax (dissipate energy into their environment) they will form a hydrogen bond, creating what is called the “water dimer”:

This configuration looks simple (an in a sense, it is) but it has been studied in an enormous number of research papers (on the order of thousands) to help better understand the hydrogen bond and to test various models.

The water dimer is the simplest example of a water cluster. There are many other water clusters , each of which exist in liquid water to varying degrees and with varying lifetimes. Some examples are :

(These examples come from the Cambridge cluster database, where you can find many more). These water clusters are a popular thing to study among chemists. Ones as large as 280+ molecules have been studied. As we can see, as more water molecules are added, new configurations are being formed, illustrating how more is different. It’s quite nontrivial to predict how x number of water molecules will arrange themselves to find their optimal configuration (lowest energy / free energy state) — the only way we know how to solve this problem is to use a computer to play with all the possible arrangements. But what happens if we bring a lot of water molecules together? Will the situation continue to be become more and more complicated?

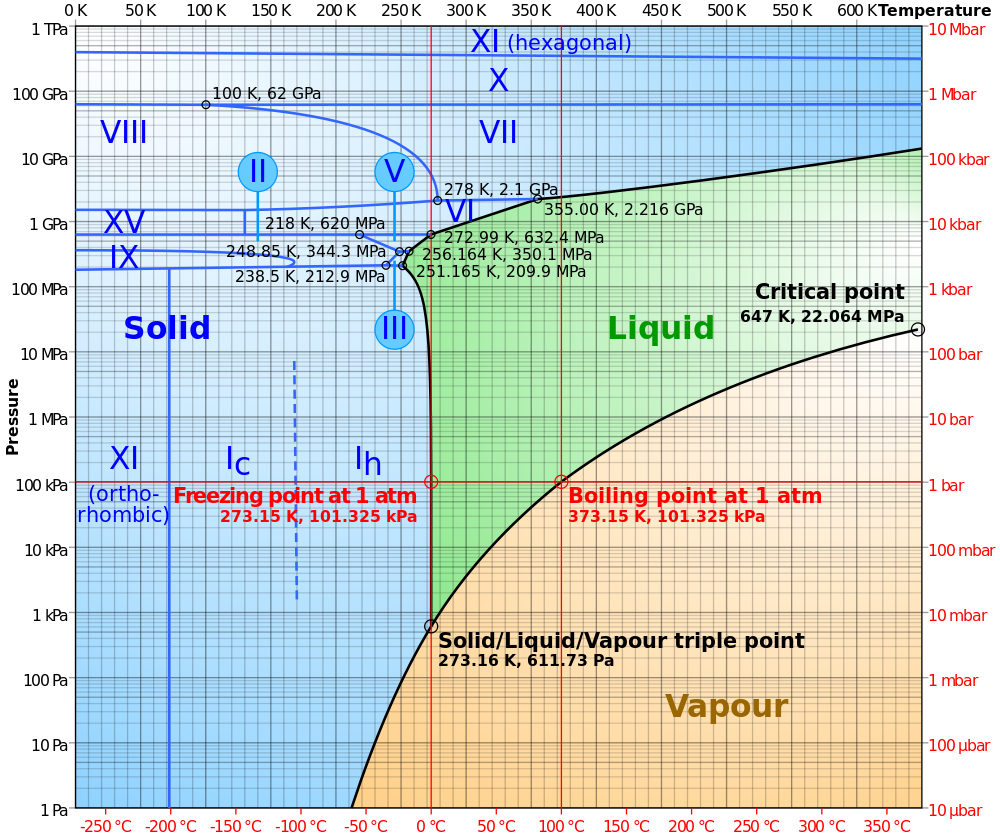

Remarkably, it turns out that when a large number of water molecules get together they form a very particular structure which is called a phase. Even more remarkably, which phase they arrive at is controlled by just two parameters – temperature and pressure – so the various phases can be plotted on a phase diagram, with temperature on the x-axis and pressure on the y axis:

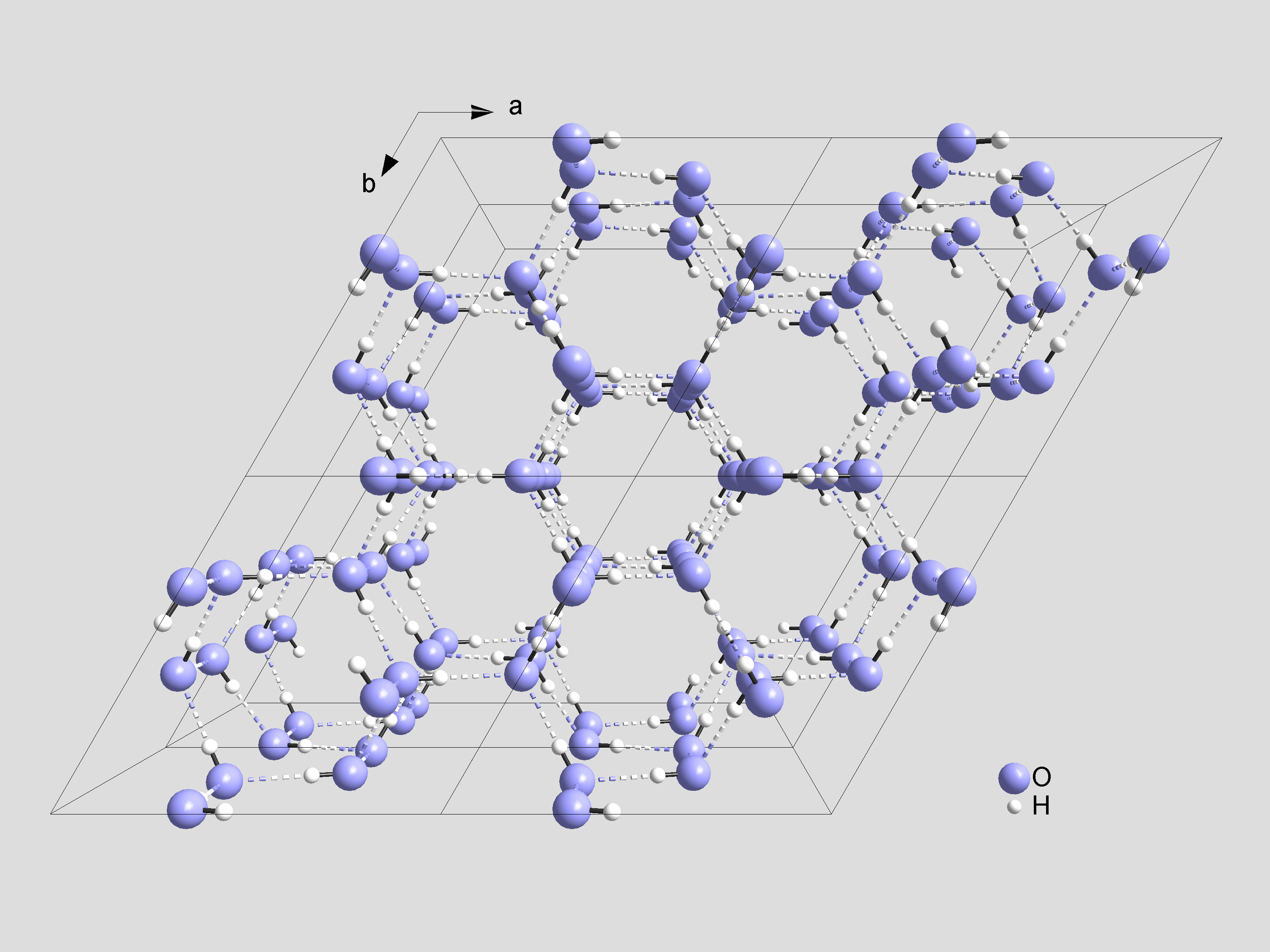

Water doesn’t have just one solid phase — so far 14 crystalline solid phases and 2-4 amorphous solid phases (not shown) have been discovered. The ice we encounter in our everyday lives is called ice Ih (‘h’ being for hexagonal) and has the following structure:

The emergence of these crystalline phases is an example of what Anderson calls “symmetry breaking”. In the crystalline phases of water, the homogeneous symmetry of empty space is replaced with a new more complex crystalline symmetry. In empty space, things look the same in all directions. In a crystal, things look different in different directions, but the arrangement observed in each direction has a very regular structure – it can be easily described as repeated copies of a small arrangement called the primitive cell.

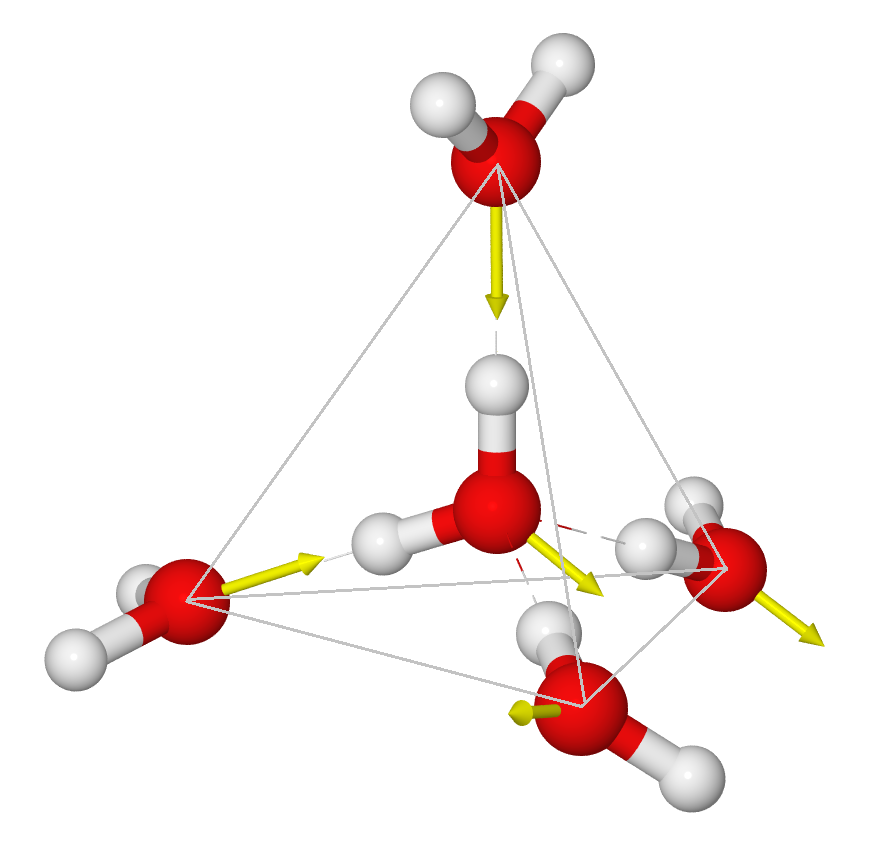

In liquid water things appear random in each direction – but they are not completely random. If we temporally average the positions of water molecules around a given water molecule, we will see that there is an average structure out to about a distance of two water molecule diameters (5 angstroms). (Beyond this there are other fainter average structures extending out to 1.5 nm and possibly going much further out – this will no doubt be discussed in a later blog post). The average structure right around a given water molecule is tetrahedral:

[In this figure, the red-white dashed lines show the hydrogen bonds, and the yellow arrows indicate the electric dipole moments of the molecules]

[In this figure, the red-white dashed lines show the hydrogen bonds, and the yellow arrows indicate the electric dipole moments of the molecules]

In his dialogue Timaeous, Plato theorized that fire was associated with the tetrahedron and water was associated with the icosahedron. If only he had it the other way around, he might have actually have been right about something.

The phases of water have their own special macroscopic properties – properties of what we call the bulk, which are independent of the properties of individual molecules, or even small collections of molecules.

Ice crystals can form into snowflakes:

And when lots of snowflakes get together, we get a blizzard.

And when lots of snowflakes get together, we get a blizzard.

Explaining how the macroscopic properties (the properties of the “more”) arise from the properties of the few is still very much a work in progress and will a remain a daunting task for a long time.

Such understanding requires studying what the molecules are actually doing to produce the macroscopic effects. This understanding is more of just academic interest – it is critically important for things like computational drug design (understanding how the water molecules interact with biomolecules) and other fields of computational chemistry where an accurate model for water is important.

However, in a very real sense, deriving macroscopic properties directly from the microscopic laws will always be an extremely difficult task. Fortunately, we don’t always need to know all the details to build theories to explain phenomena at the macro scale. As Anderson discusses, at each new level of complexity, new simplicities emerge – the crystalline structures of ice and the phase diagram being one example. The friction between ice and rock is well characterized by a single number — deriving this number from the microscopic properties of the ice and rock would be very difficult, but we’ve measured that number in the lab, we can go on to build theories about other things, such as how glaciers move.

In the 20th century, the emergence of molecular biology has added a new level of research into biology, and is proving to be an extremely rich field due to the fact that more is different. In molecular biology, we see molecules arranging themselves in miraculous ways, such as the self assembly processes of micelles and the folding of proteins. As Anderson says, the arrogance of the particle physicists in the early 20th century , one of whom famously declared that after physics everything else was stamp collecting, is analogous to the arrogance of molecular biologists in this century, who believe that all life processes can be neatly broken down into chemical reactions. Proteins and enzymes interact in extremely complex ways, forming a network which can can be understood using a new area of fundamental research called network science. Cells, as well, interact in complex ways that are just being understood, through a variety of chemical and electrical signals. The number of levels of hierarchy between biomolecules and something the complex as human thought remains to be seen, but certainty, much more will be required to understand the human brain than just an understanding of the chemical reactions which take place inside.