Does hot water freeze faster than cold? Explaining the Mpemba effect

In this article I would like to lay the following question to rest:

“Does hot water freeze faster than cold?”

The answer is:

“Yes, in some cases.”

In the rest of this article I will explain what these cases are and why the phenomena of hot water freezing faster than cold is not as mysterious as some have made it out to be.

A bit of history

I do not have room here to discuss the long history of this problem, which goes back to Aristotle, was pondered by Thomas Bacon and was more recently revived by a student in Africa named Erasto Mpemba. [For this reason, it is sometimes called the Mpemba effect, even though Mpemba was studying sugared milk during ice cream preperation and not water in his experiments.] While long discussions of the history of this subject are common (see reference 1), I feel that discussing the historical narrative is counterproductive to the point I wish to get across. The standard historical narrative on this subject gives the impression that this is a ‘great mystery’ which has stumped scientists through the ages. The truth is that this phenomena has stumped many great thinkers, but careful experiments on this phenomena have only been carried out very recently. My hope here is to convince you that this phenomena is actually not very mysterious (although it is a bit complicated), and then if interested you can read the historical narrative afterwards from that perspective.

The motivation:

I exhort you to try the following experiment: take two identical containers, fill one with hot water and one with cold, and place them in the freezer. [If you are worried about contaminants, feel free to thoroughly wash your containers and use distilled water] Check them periodically for the formation of ice. Usually the ice will start to form at the surface.

There is a very good chance that the hot water will freeze first. In most cases, the reason for this can be explained as follows:

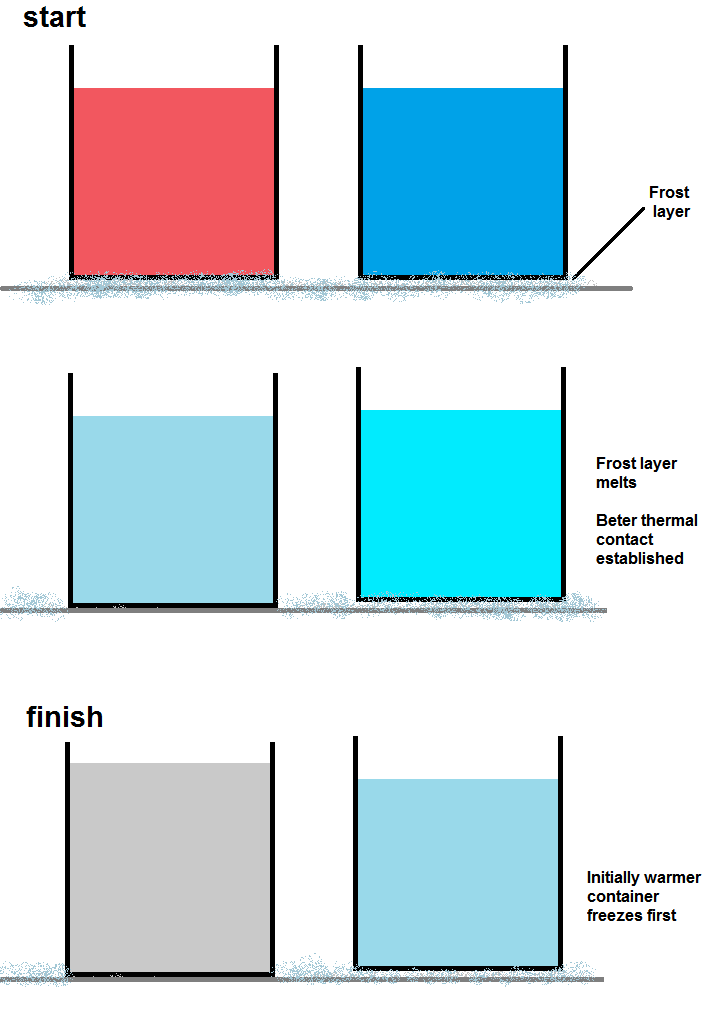

In almost all freezers, there is a thin layer of frost coating the inside of the freezer. This frost is a very good insulator. The hotter container will quickly melt this layer of frost, allowing good thermal conduction between the inside of the freezer and the container. Once this good thermal contact is established, the container of hot water will cool much faster than the container of cold. There is additionally another problem with this setup – the containers are open, so more hot water will evaporate than cold. Because of this, the hot water container will end up with a lower mass than the cold and thus will not take as long to freeze completely solid.

There is additionally another problem with this setup – the containers are open, so more hot water will evaporate than cold. Because of this, the hot water container will end up with a lower mass than the cold and thus will not take as long to freeze completely solid.

But what about identical containers under identical conditions?

** At this point it is clear there is a problem with most freezer experiments people do at home: they don’t keep the two containers under identical conditions. As we will see, this is a problem which is very difficult to avoid. To emphasize that we want the containers to be under identical conditions , let us more precisely state the question we wish to answer:

Given two identical containers of pure water, one at a temperature T1 and one at higher temperature T2 > T1, if these containers are cooled under identical conditions, are there initial temperatures {T1, T2 : T2 > T1} where the onset of freezing occurs first in the container which was initially at T2?

Notice how the problem is carefully stated. The difference in initial temperatures (T2-T1) is not stated. Obviously, if one container starts at 1C, while the other is at 99C, the 1C container will freeze first. A more interesting case to try would where one is initially at 90C and the other is at 65C. Also notice that we are interested in when the onset of freezing occurs. Freezing does not occur instantaneously – rather, it starts at a particular location, called the nucleation site, and then propagates outward from that site. Furthermore, it is very difficult to cool water uniformly. A standard freezer doesn’t do a very good job since usually the cold air from the freezer comes from a particular direction. Because water has a maximum density at 4C, once some parts of the water are cooled below 4C, the cooler water goes to the surface because it is less dense. Thus freezing usually begins near the surface and then propagates downward. This is exactly what is seen in lakes during the winter. However, where freezing starts also depends where the good nucleation sites are. If the best nucleation site is at the bottom of a container, freezing is more likely to start there.

Since in any real world refrigerator the cooling process will never be 100% perfectly uniform, there are always movements of water called convection currents. While the water is above 4C, there will be normal convection, the hotter parts will be less dense and will move upwards, while the cooler parts will move down. Once parts of water are cooled below 4C, the opposite will start to occur – the cooler parts (below 4C) will move up and the warmer parts will move down. The process of convection continues after the onset of freezing. Because of convection, the dynamics of freezing are very complex. Additionally, as ice forms, it acts as an insulator. Depending where the freezing starts, the insulation of the ice can greatly effect how quickly the rest of the water freezes.

By defining the problem in terms of the onset of freezing, we can neglect the complicated process of freezing itself.

Additionally, it much easier to measure when the freezing starts than to try to measure the precise moment when all the water is frozen. This is because at the precise instant when ice crystals start to form, the system begins to release latent heat. [more on this in a bit]

Of course it is still quite possible that the onset of freezing will occur first in the cold water, but the entire body will freeze first in the initially hot water. [Something like this is thought to occur in the related phenomena of hot water pipes freezing solid before cold. ]

Some good experiments

Many scientific experiments have been done on the Mpemba effect over the years. I looked over several articles from the older literature [1960-1970s] a while ago and found them to be confused. Some found an effect, but admitted their experiments had possible flaws, and others were inconclusive. I will not try to summarize them here. Instead, I will focus on a series of very careful experiments performed by Dr. James D. Brownridge at SUNY Binghamton. I believe they are by far the most comprehensive set of experiments done on the subject.[ I also took the overarching ‘solution’ to the problem from his exposition.]

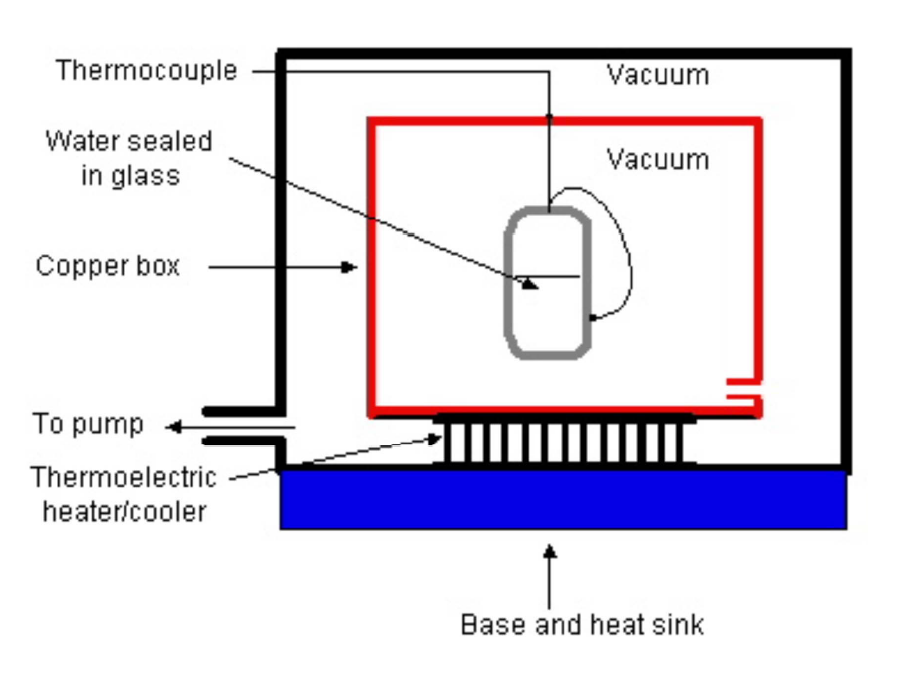

In his most recent round of experiments, he took ultra-pure samples of distilled water and sealed them in small glass vials. The vials were then suspended by threads in a vacuum and cooled using radiative cooling. The nice thing about this method of cooling is that it completely removes the possibility of a difference in the thermal contact between the hot & cold vials and ensures that they are all cooled in exactly the same fashion. Furthermore, the cooling is very uniform and reproducible.

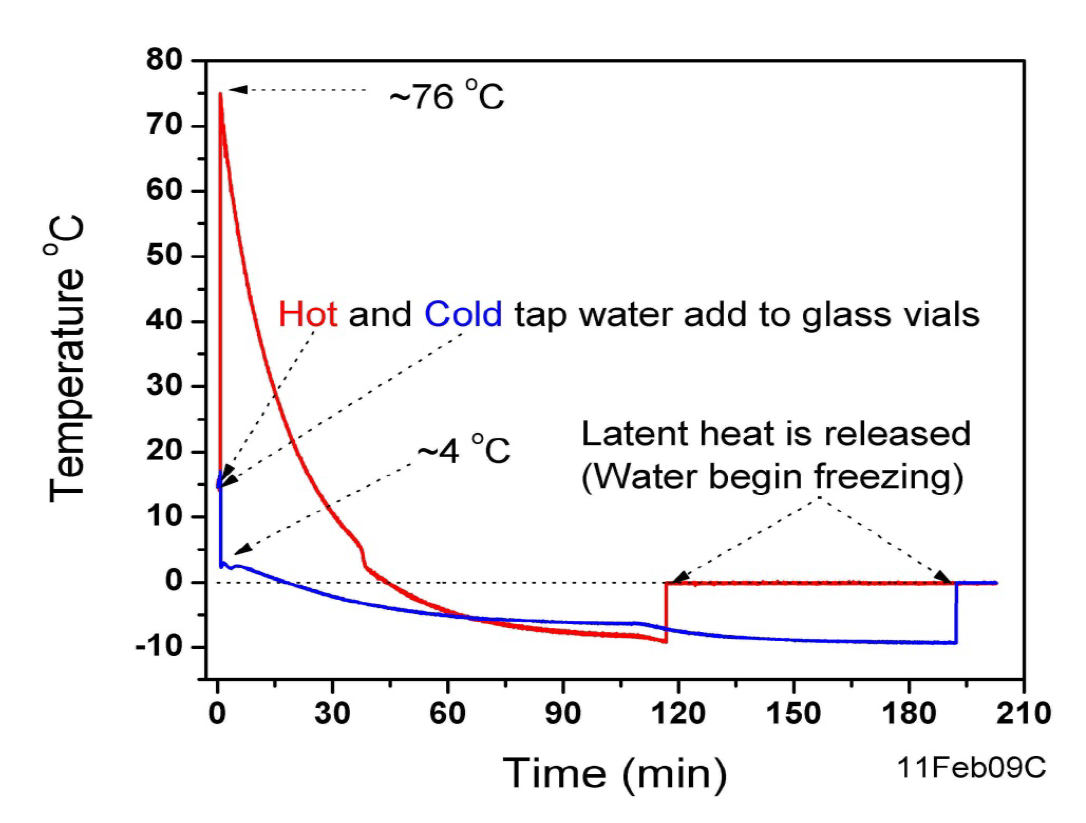

A small thermocouple measures the temperature as a function of time to high accuracy. Here is an example of two sets of data, comparing hot & cold water:

Notice that both the hot & cold water are cooled below 0 C – this is called supercooling, and it happens very easily in water, especially when the container is very clean.

Also notice that the onset of freezing appears as a sharp jump in temperature to 0 C. This is the release of the latent heat which was mentioned before. During crystallization the molecules move to configurations with less potential energy [or more technically, lower free energy]. This potential energy is lost into heat. However, perhaps counter intuitively, the temperature of the water remains at 0 C during the freezing process.

Why does the temperature remain at 0 C during the freezing process, if molecules are radiating heat ? Consider one molecule which just fell into the lower potential energy configuration (the ice phase) – it radiates the energy it lost to its environment (either through a collision or by emitting radiation). This heat is absorbed by other molecules, allowing them to jump the barrier into the lower energy configuration. This process continues until all the molecules have jumped the barrier into the lower energy configuration (ice). While this is happening, heat is also radiated to the external environment, in this case to the cooling device. The cooling device pumps this heat out of the system. During freezing there is an equilibrium established where the rate that the latent heat is being released equals the rate the refrigerator is able to pump the latent heat out. If this was not the case, the sample would heat above 0 C and freezing would stop. Thus, the system remains at 0 C until all the ice is frozen. After freezing, the sample continues to cool below 0 C.

So what was the outcome of Brownridge’s experiments? The outcomes were mixed – in some cases the hot water vial would freeze first but other times it was the cold one. But at all times, the hot vial always remained warmer than the cold. [The first plot does not show this, but it comes from an earlier set of less careful experiments. The slight kinks in the data are cause for concern in this data and revealed a flaw in how the vials were set up.] He also noticed that a given vial always would freeze at the same temperature, no matter how many times he repeated the experiment. This makes sense when one considers that each vial will have different nucleation sites inside of it. Each nucleation site has a nucleation site temperature, which is the temperature at which it will cause freezing. The highest temperature nucleation site [HTNS] determines the temperature water will freeze in a given vial. Comparing what appear to be identical vials, the HTNS are random and they can be between anywhere from 0 C to -45 C. -45 C is the lowest it is possible to supercool water — at this temperature, called the homogeneous nucleation temperature, water becomes thermodynamically unstable and will freeze solid all at once,even without any nucleation sites. In practice, the HTNS’s of Brownridge’s vials seem to have been between 0 and -20 C.

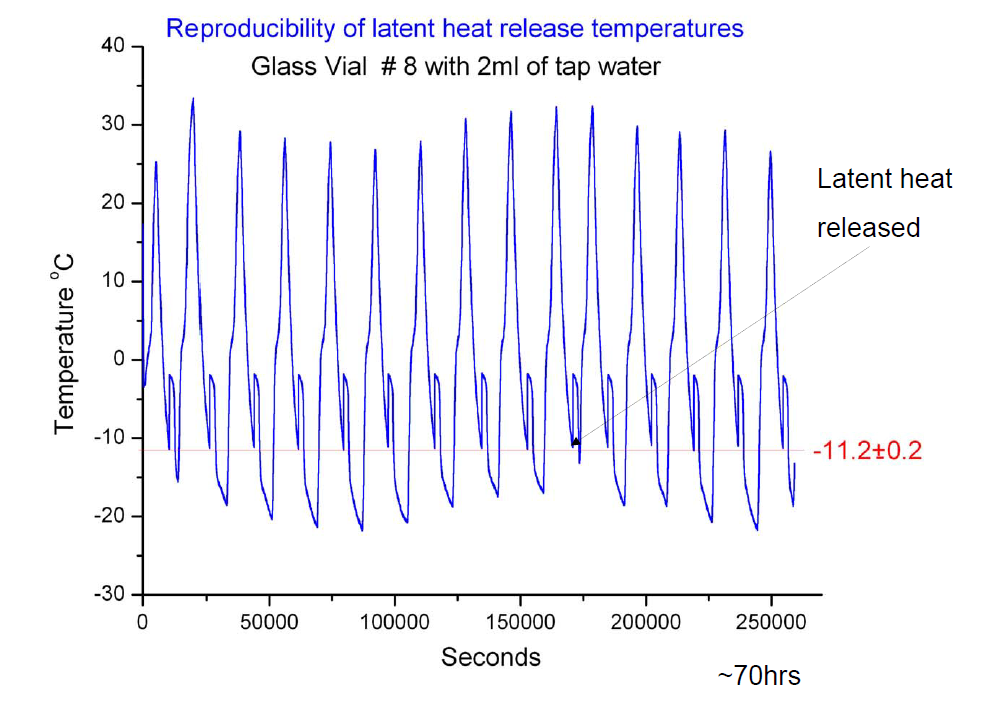

The HTNS is a constant of the container. Brownridge showed that it doesn’t change with time, by freezing and thawing the sample many many times:

In this case, the HTNS of the container was -11.2 C. Brownridge also kept a sample super cooled at -15 C for 422 days, just to show that the water will not spontaneously freeze!

With this concept at hand, we can now understand why hot water sometimes freezes before cold in these experiments – it can occur when the HTNS of the hot water vial is higher than the cold water vial.

In particular, Brownridge says that the HTNS of the hot water vial must be about 5 C greater than the HTNS of the cold water vial in order for it to freeze first.

You might wonder if the nucleation sites are on the wall of the container or actually dissolved in the liquid. I asked Brownridge this question at a conference I attended in the fall, and he said he is pretty sure they are on the walls of the container. In one of his presentations he has frames from movies of freezing which show exactly where the freezing starts. In the two cases he shows, the freezing starts on the wall of the container, indicating the nucleation site was located there.

Conclusion

In conclusion, hot water can freeze faster than cold, but only when the containers are not identical. The difference in the containers can be something dramatic, like different thermal contact, or it can be something subtle, like different nucleation sites.

If the two containers were absolutely identical [which is impossible, because they will always have slightly different molecular structures & thus different nucleation sites], and absolutely free from impurities [which is very difficult], there is no good reason theoretically to believe hot water would freeze first.

There are theories giving a mechanisms whereby hot water might freeze first in identical containers, [such as the ‘faster supercooling’ theory] but experiments seem to rule these out quite conclusively. Such theories have not been accepted by the scientific community as far as I can tell. After all, they fly in the face of the basic laws of thermodynamics.

References:

1.Jeng, Monwhea. “The Mpemba effect: When can hot water freeze faster than cold?” Am. J. Phys. 74 (6), pp 514 (arXiv.org) – Excellent historical discussion**

2.Brownridge, J. “When Does hot water freeze faster then cold water? A search for Mpemba Effect” Am. J. Phys, (2011) 79 (1), pp. 78 (arXiv.org) – the best experimental paper

-

Katz, J.I. “When hot water freezes before cold” Am. J. Phys. (2008) 77 pp. 27–29 (arXiv.org) – postulates that earlier experiments were contaminated by solutes, either gaseous or solid and provides a mechanism for how dissolved solutes can lead to the effect.

-

Auerbach, David. “Supercooling and the Mpemba effect: When hot water freezes quicker than cold” Am. J. Phys. (1995) 63 (10) pp. 882. – an earlier experiment finding results similar to Brownridge’s and confirming the analysis presented here.

More information:

Dr Brownridge’s webpage with links to his presentations

Can hot water freeze faster than cold water? – a very thorough exposition, including the history and references to older experiments. It also touches on the issue of dissolved gases, which I choose to skip for brevity.