Polyhedra

Polyhedra have fascinated people for a long time. With their straight edges and flat faces, they appeal to human’s desires for order and perfection. Their physical manifestations are almost always a product of human thought and intellect.

Plato was definitely a polyhedra fetishist. The polyhedra he promoted are probably the five most famous polyhedra in the world today. No serious nerd hasn’t heard of the cube, tetrahedron, octahedron, dodecahedron and icosahedron. These polyhedra are so cool, Plato thought all matter must be made up of them – a famous theory which people bought into for centuries and is today is still lauded in history & philosophy classes as grade A BS.

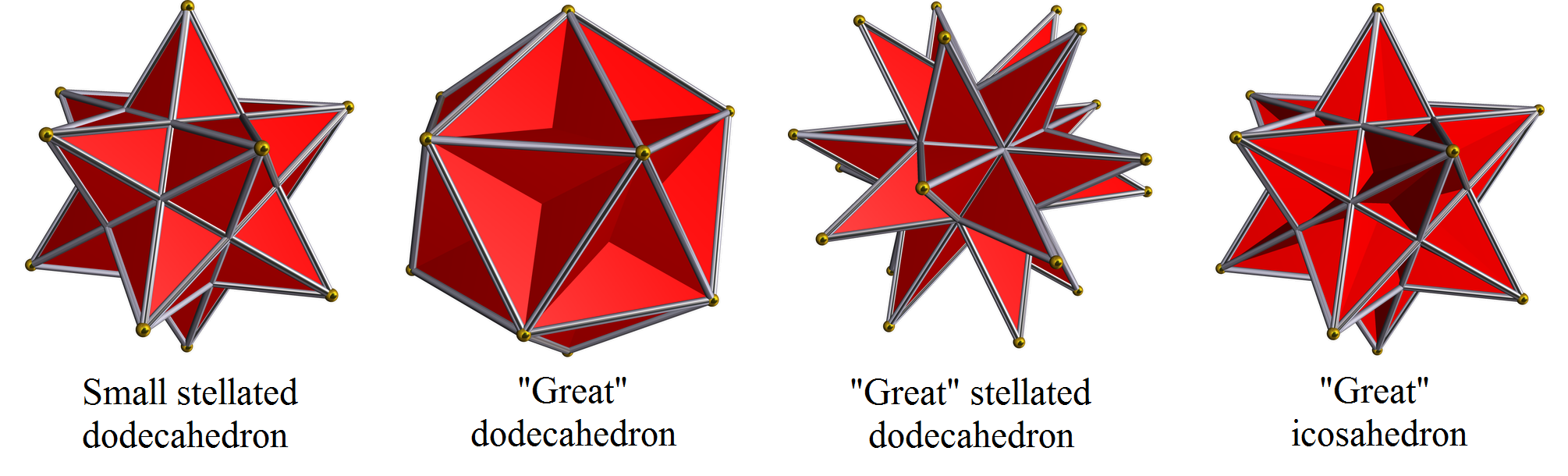

These Platonic solids are indeed special, or as mathematicians like to say, “regular”. The term “regular” means all their edges and all their angles are identical. They are also the only polyhedra which have their vertices lying on a sphere. The Platonic solids are the only regular polyhedra, along with four other polyhedra which nobody seems to give a hoot about:

These four forlorn children the polyhedral universe are the Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra. While it’s likely some medieval monks with too much time on their hands discovered some of them, these guys were not recognized as being regular until Kepler discovered that fact in 1619. Apparently though, not many people really cared, because they had to be rediscovered in 1809 by a French physicist named Louis Poinsot. Three years later in 1812 the great mathematician Augustin-Louis Cauchy proved that the Platonic solids + the Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra were the only regular polyhedra in three dimensions thus preventing someone from one-uping both Kepler and Plato. Altogether there are five convex regular polyhedra (Platonic solids) + four concave polyhedra , yielding 10 regular polyhedra in three dimensions. In four dimensions there are six, and then in five and higher dimensions there are only three. In 2 dimensions there are an infinite number corresponding to the n-gons.

In addition to these forlorn children, I want to introduce some other polyhedra that are under appreciated. The polyhedra I want to discuss are space-filling. This means that you can tessellate (ie. stack) them and they will fill space with no gaps! Of the Platonic solids, only the cube has this property. Aristotle however thought the tetrahedron fills space, just showing why you can’t always trust the wisdom of the ancients. (It amusing to wonder how long it was before someone bothered to check if Aristotle was right by actually taking some tetrahedra and trying to fill space with them. Apparently it didn’t happen in his lifetime – as is typical of Greek “science”, they didn’t bother to check most things experimentally, especially when it was coming out of the mouth of somebody as famous as Aristotle.)

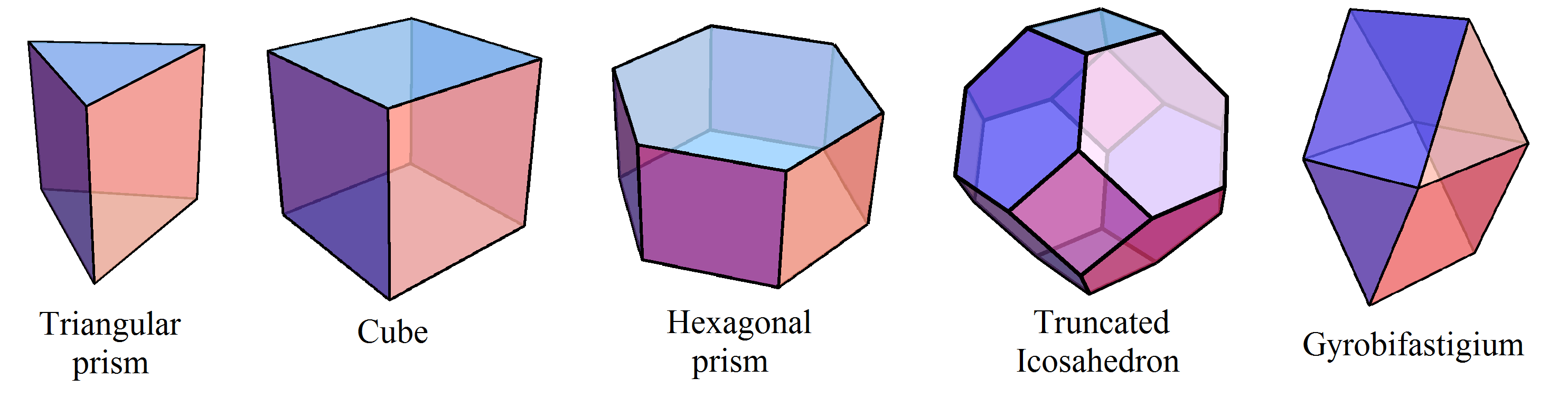

There are five space filling convex polyhedra that have regular faces: the triangular prism, hexagonal prism, cube, truncated octahedron and the weird-ass gyrobifastigium:

In my opinion, these are not the coolest space filling polyhedra. What I’m interested in is space filling polyhedra that fill space in a similarly situated way. In other words, you don’t have to rotate them while you are stacking them.

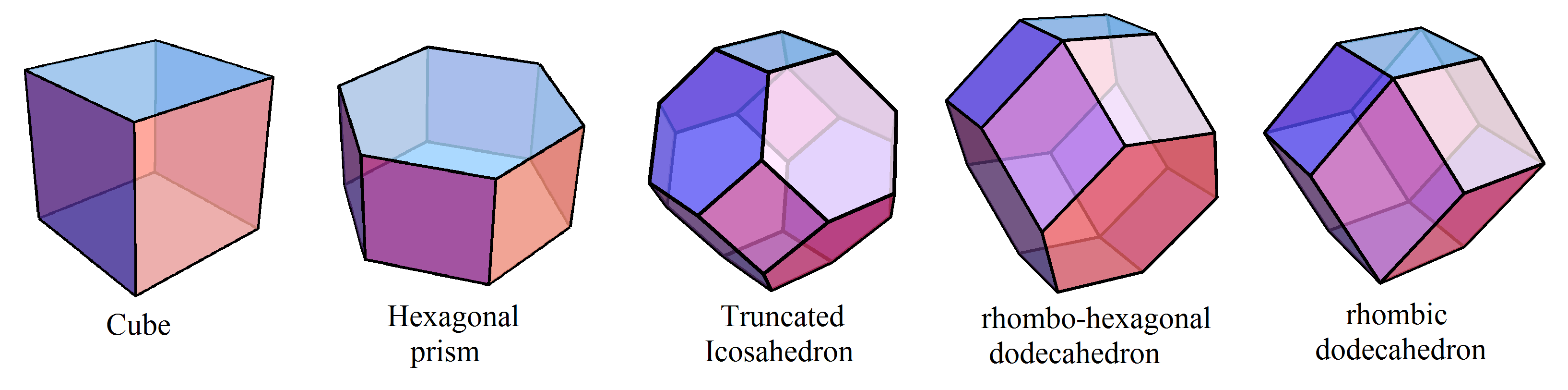

Once again, there are only five polyhedra with this property: the cube, hexagonal prism, rhombic dodecahedron, rhombo-hexagonal dodecahedron, and truncated octahedron

[Note for physics nerds – these five polyhedra come up a lot in solid-state physics, because they form the Wigner-Seitz cells (or Brillioun Zones, in k-space) for the cubic, hexagonal, FCC, body centered tetragonal and BCC lattices respectively. Those are all very common crystal lattices!]

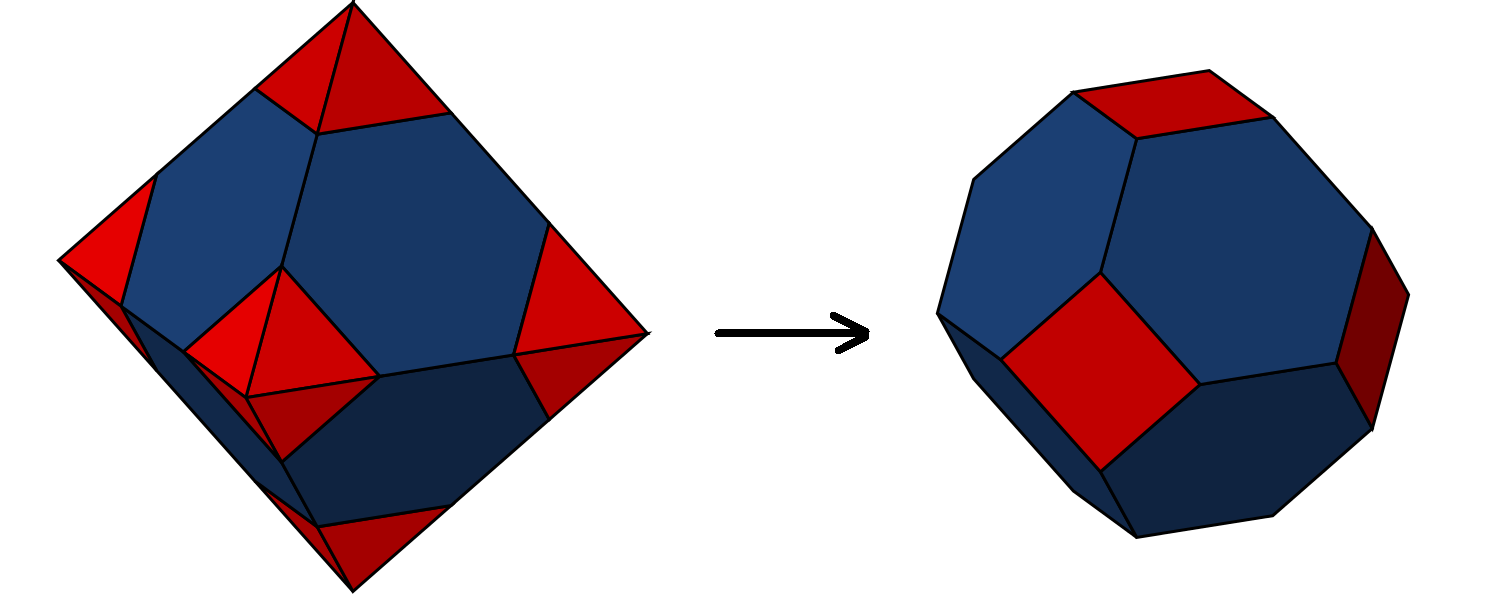

Of these, the truncated octahedron is definitely my favorite. The rhombic dodecahedron is also pretty neat, but the construction of the truncated octahedron is much easier to visualize — simply take an octahedron and chop off the corners:

It’s also to see how these fill space:

By now some of you may be wondering what this has to do with my research. If so, stay tuned because that shall be revealed in the next post! If not, I hope you at least enjoyed the pretty pictures.