Periodic Boundary Conditions

As promised , I shall now reveal why I had a bout of interest in polyhedra, as discussed in my last post.

(Sorry for those of you who were waiting on the edge of your seats for three weeks)

It all has to do with periodic boundary conditions (PBCs).

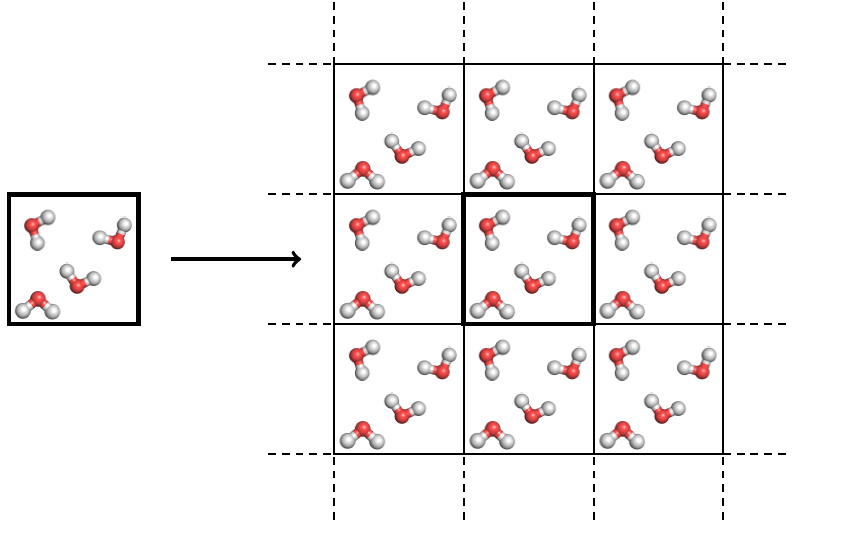

When people do molecular dynamics simulations, for instance of water, they simulate a certain number of molecules. In the field of water research I am in, typically people will simulate around 128 – 512 water molecules. (for some arcane reason, people like to use powers of 2). In biophysics simulations of biomolecules in water 10,000 to 100,000 water molecules may be called for. These simulations are not done in ‘boxes’ where the molecules bounce off the walls, instead they are done with periodic boundary conditions.

The easiest way to understand how PBCs work is to play the game Asteroids. When an asteroid or spaceship reaches one side of the box, it re-enters on the opposite side. The same thing happens in a molecular dynamics simulation, except instead of asteroids, one has molecules.

This is great, because it means that there are no walls and no surfaces. Water molecules behave differently near surfaces (either a vacuum or a wall), creating special structures. In fact, when water is simulated in a box with walls, the water molecules near the walls create pressure on the water molecules in the simulation box. [This is called Laplace pressure – for instance, if 100,000 water molecules are confined in a nanocavity, they will behave much different than normal water, partially because of this extra pressure. Such ‘nanoconfined’ water has been a hot topic of research of late and there were dozens of talks at American Physical Society March Meeting devoted to the topic.)

There is a difficulty with this approach though when it comes to treating the Coulomb (electric) interactions between molecules. The problem is that one must account for interactions between molecules that occur at distances which are greater than the size of the simulation box in order to accurately describe the forces water molecules experience in real water. This is especially true for polar molecules like water molecules which have non-zero electric dipoles. The problem is solved using something called Ewald summation, a modern incarnation of mathematical techniques developed by Madelung in 1918 and Ewald in 1921 to calculate the potential energy of ions in crystals.

I won’t go into the technical details of Ewald summation — the important part is that it creates many ‘replicas’ of the box arranged in a periodic fashion. Ewald summation gives the exact energies/forces for this periodic system, which makes it great for analyzing systems which are naturally periodic, like crystals. Liquid water is of course, not periodic though, so this is cause for concern.

Because of this concern people have investigated using other boxes besides cubes for non-periodic systems like water. Essentially, we need a polyhedra with nice regular polygon sides which fills space and does so in a regular way (a similarly situated fashion). As discussed in the last post, there only five types of polyhedra (in three dimensions) which fulfill these criteria: the cube, hexagonal prism, rhombic dodecahedron, rhombo-hexagonal dodecahedron, and truncated octahedron.

Out of these the cube is still the most used because it is really easy to implement the PBCs, and in many applications the cube is perfectly fine. The hexagonal prism is useful for simulating very long molecules, like DNA, in water – otherwise simulating DNA in a cube would require adding many more water molecules than are necessary, increasing the computational cost of the simulation. Of the remaining polyhedra, the rhombic dodecahedron is the most used, followed by the truncated octahedron. The rhombo-hexagonal dodecahedron is never used and there really isn’t any good reason to use it.

When deciding between the rhombic dodecahedron & the truncated octahedron , three factors are important:

The first is the computational complexity of implementing the PBCs. The box PBC calculation is very short , while the code for the truncated octahedron is considerably longer, and the code for the rhombic dodecahedron is even longer. (the codes are available for inspection here) PBCs are calculated a lot in molecular dynamics, so making the PBC code fast is something to worry about.

The second factor is the radius of the largest inscribed sphere. One would like this radius to be as small a percentage of the spacing distance as possible because interactions are treated with a spherical cutoff. Another way to think about this is to consider if you were doing a simulation of a protein and you wanted to solvate it (surround it) with 1.5 nms of water molecules. Doing this in the rhombic dodecahedron requires less total water molecules than in the cube or the truncated octahedron. For this reason the rhombic dodecahedron box is heavily used in biophysics. [the reduction in computational cost due to having less water molecules offsets the computational cost incurred due to the more complex PBC routine]

The third factor of importance is the sphericity of the polyhedra. One would like the polyhedra to be the most ‘spherical’ in some sense, to reflect the isotropy of water (ie. the spherical symmetry of water).

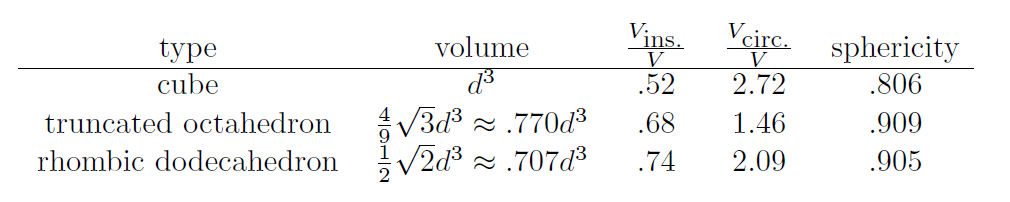

It turns out there are several different measures mathematicians have devised to quantify how spherical a polyhedra is. In the following table I compare two measures:

One of measures is to look at the radius of an circumscribed sphere (the smallest possible sphere which fits around the polyehdra). Then, compare the volume of this sphere to the volume of the polyhedra. The smaller the ratio, the more spherical it is. By this measure, the truncated octahedron is much more spherical. The other measure is called sphericity, and is defined as ratio of the surface area of a sphere with the same volume as the polyhedra to the surface area of the polyhedra. By this measure, the truncated octahedron is just slightly more spherical than the rhombic dodecahedron.

One of measures is to look at the radius of an circumscribed sphere (the smallest possible sphere which fits around the polyehdra). Then, compare the volume of this sphere to the volume of the polyhedra. The smaller the ratio, the more spherical it is. By this measure, the truncated octahedron is much more spherical. The other measure is called sphericity, and is defined as ratio of the surface area of a sphere with the same volume as the polyhedra to the surface area of the polyhedra. By this measure, the truncated octahedron is just slightly more spherical than the rhombic dodecahedron.

I have recently done some simulations with 28,000 water molecules in a cube, 20,000 in a rhombic dodecahedron and 21,000 in a truncated octahedron. I will be comparing the long-range dipole correlations, for which artifacts appear due to the PBCs. The artifacts are greatly reduced by using the rhombic dodecahedron and may be further reduced by the truncated octahedron. Unfortunately, though the analysis program I am running will take 40 days! I need to either parallelize the code, wait 40 days, or figure some way to make the program faster.