Is Tesla’s particle beam weapon practical?

During the later part of his life, Tesla made grandiose claims about having invented a “death ray” or “teleforce” weapon, the plans for which were discovered in 1983. In more prosaic terms what Tesla designed is a neutral particle beam weapon. Many Tesla fanatics claim that during the cold war the US government and/or USSR conducted tests of such weapons based on Nikola Tesla’s designs. Some insist that the US government is in possession of such weapons in some undisclosed facility, while others claim Tesla took the secrets of such technology to the grave for fear that they would fall in the wrong hands. In this post, I will investigate whether the type of weapon Tesla envisioned is practical.

To get my readers up to speed on this topic, here is quick timeline of known historical events. I highly recommend reading the full account in Bernard Carlson’s new book, Tesla: Inventor of the Electric Age. Tesla’s claims about particle beam weaponry constitute one of the most interesting sagas in Tesla’s life and Carlson does a great job of referencing primary source materials on what is known to have transpired.

1934 – Tesla, now an old man of 78 years, claims to a New York Times reporter that he is working on a particle beam weapon that will “bring down a fleet of 10,000 enemy airplanes at a distance of 250 miles”. The report gains enormous amounts of publicity. The new spectre of aerial bombardment has the citizens of many countries scared and government and military officials are scrambling to find a means of defense against attack from the air. The idea of a particle beam weapon looks attractive to world leaders.

1934 – Sensing a business opportunity, Tesla commissions architect Titus deBobula to draw plans of what the new particle beam weapon towers might look like and contacts several governments around the world to try to sell his plans.

1935 – US State Department officials are warned by the US ambassador to Italy that Tesla may soon offer his plans to the League of Nations, raising the possibility that all European powers may soon be in procession of beam weapons of unimaginable destructive ability. The ambassador argues that the US government needs to gain control of the plans and prevent them from falling into the hands of any other governments so the US can act as a ‘peaceful guardian’ over such weapons. The State Department acknowledges it holds responsibility for the fate of the plans but is not known to have done anything else.

1935 – Using an underground dealer, Tesla sells plans for a particle beam weapon to the Soviets for $25,000. The plans are studied by Soviet scientists but it is not known whether they constructed and tested any prototypes.

1936-1938 Tesla offers to sell his designs to the British government for a cool $30 million. Correspondence between Tesla and British officials continues until 1938 when ultimately the British decline to pursue Tesla’s plans further.

~1937 Tesla claims to a reporter that his apartment was broken into and his papers examined. He claims that the spies left empty handed, though, since there are critical details about the weapon which he has not committed to paper, but carries around in his head instead.

1939 – WW2 begins. Tesla attempts to gain funding to build his particle beam weapon from the US government, but is denied.

1940 – Seeking publicity, Tesla announces a new beam weapon idea which he calls “teleforce”. No details are given, however.

1943 – Tesla dies. The FBI uses the Office of Alien Property Custodian (OAPC) to seize Tesla’s papers, setting off decades of speculation about a coverup. According to the FBI, the papers were carefully analyzed by John G. Trump, a RADAR scientist at MIT, along with several high level Naval Intelligence officials. Trump declares that the papers do not contain any new information which would “constitute a hazard in unfriendly hands” and the papers are deemed safe to be released. Trump includes an analysis of Tesla’s particle beam papers in his report, concluding that the plans do not contain enough information to actually build a weapon and that any workable configuration would be of very limited power.

1943 – Tesla’s papers are released from FBI custody but are quickly seized and locked up the New York Department of taxation since Tesla had a large outstanding tax obligation.

1945 – Bloyce Fitzgerald, only an army private, contacts the FBI and asks for Tesla’s papers. He claims he is heading up a top secret research project at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio. The FBI says that it does not know of any Tesla papers or microfilms held by it or any other government agency. Conspiracy theories exist to this day that Wright Field was used to test a version of Tesla’s weapon.

1951 – The Yugoslav government pays Tesla’s back taxes, and the Tesla papers are shipped to Belgrade to be part of the Tesla Institute & Museum.

1977 – General George J. Keegan claims that the Soviets are building a large scale particle beam weapon at the Semipalatinsk site in Kazakhstan, prompting fears of a “death beam gap” among the public. In an attempt to allay these fears, President Carter and scientific experts deny the allegations. After the Cold War, American experts visit the site and conduct an investigation, concluding that the site was used to research the possibility of nuclear-powered rockets. Keegan’s claims are decried as “one of the major intelligence failures of the cold war”.

1983 – A paper surfaces which is the first to show an actual plan for a weapon. An analysis of the paper by the Tesla museum in Belgrade determines them to be authentic. The paper, which is entitled The New Art of Projecting Concentrated Non-dispersive Energy through Natural Media is the only known paper Telsa ever wrote about particle beam weaponry.

1981 – The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) is announced publicly.

1989 As part of SDI, researchers develop neutral beam technology at Los Alamos National Laboratory, with the intent of using a particle beam weapon in orbit to disable space-based systems. As part of the Beam Experiments Aboard Rocket (BEAR) project, a prototype hydrogen beam weapon is launched from White Sands Missile Range in July 1989 and successfully deployed into low Earth orbit. It is operated successfully in space and is recovered after reentry.

2006 The BEAR weapon prototype is transferred from Los Alamos to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

Difficulties in building a particle beam weapon

There are major differences between the space-based particle beam weapon tested during the cold war and the type of weapon Tesla envisioned. First of all, a large portion of the the design plans Tesla presents are not for the accelerator itself (which is a rather simple device, similar to the cathode ray tubes found in old TVs) but for the high voltage generator he envisions to power it, which is essentially a highly modified van de Graaf generator (picture a van de Graaf, but one that uses circulating air in tubes instead of a belt to transfer charge). I will not dwell on this hypothetical van de Graaf, since we now have other ways of generating high voltages. I will also not dwell on Tesla’s particular accelerator design, since it has since been supplanted by vastly superior designs. Instead, I will ask if the the general principle – using a neutral particle beam as a weapon – is feasible.

The acceleration of charged particles using electrostatic fields is utilized in many different devices, ranging from the cathode ray tubes found in the back of old tube televisions to particle accelerators found in hospitals and research labs. There are several difficulties with weaponizing such beams, however.

Let’s consider some of the obvious technical challenges first. Unlike particle accelerators, which use charged particles, a particle beam weapon must fire neutral particles, otherwise (due to conservation of charge) parts of the weapon rapidly acquire the opposite charge of the beam causing the device to fail. This situation can be overcome by first stripping electrons off of atoms, creating positive ions which can be accelerated. Then, as the ions leave the accelerator, electrons are injected into the beam, forming a neutral beam. Telsa proposed mercury ions but does not describe any method for neutralizing the beam (as far as I can tell). (The concept of a mercury beam is particularly terrifying- since in addition to boiling the blood of soldiers, it would also poison them.)

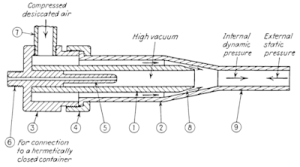

The next problem is that particle beam acceleration has to take place in a high vacuum. If a beam is not accelerated in a vacuum, the accelerated particles scatter off air molecules and in one way or another destroy the accelerator. To weaponize such beams, however, the beam needs to be able to leave the accelerator through a hole so it can travel through the air to the target.(Note, in outer space, this is not a problem!) Tesla designed a rather clever ‘vacuum tube’ nozzle which uses a stream of compressed gas to maintain the ultra high vacuum inside the accelerator tube while facilitating the transfer of the beam into the atmosphere. The use of a such a nozzle is problematic, however. The first issue is that it isn’t clear if it could actually work without the high pressure gas scattering the particles haphazardly. The second problem is that the beam must be very carefully collimated and aimed – a tiny error in beam alignment would cause the particles to hit the walls of the nozzle. As mentioned here, particle beams usually contain a substantial “halo” of additional charged particles (at least, that’s the case at the LHC). In any case, the use of a nozzle requires that the beam have a very small diameter. To destroy an object with such a narrow beam, one would have to use “cutting” motions to cut targets into pieces – merely poking a hole through a tank or plane is unlikely to disable it. This is not as useful from a military standpoint, since it requires extremely precise tracking and aiming. It would be better if the beam could be aimed to destroy a plane or boat in one shot, as Tesla imagined.

The amount of energy a beam can deliver to a target per second is called the power of the beam, measured in Watts. The power of the beam depends on the mass of all the particles in the beam, their velocity, and the dwell time of the beam on the target.Tesla imagined that his weapon could kill enemy soldiers by “boiling their blood”, a process, which, according to Paul Nahin requires a minimum of 36,960 Watts (this is assuming absolutely no shielding on the soldier). Carlson uses this figure to illustrate the impracticability of the accelerator, arguing that the power consumption requirements would be too large. [Indeed, Tesla boasted that his device could destroy an army of one million soldiers, which would require a power of 36,960 MW, or the equivalent of ~36 nuclear power plants.]

Let’s assume that the beam density (number of particles per meter) is similar to that produced by the LHC, the most powerful particle accelerator in the world (this appears to be ~ 3.83*10^8 protons per meter) . This is probably overly generous — beams of such high density are very hard to maintain (charged particles like to repel each other), and require sophisticated beam “bunchers”.

Cutting through human bone requires a 3 W laser at minimum. Again assuming LHC beam density, a simple calculation shows this requires a 23 keV beam. A beam of this power (only ~10 times more powerful than an old TV tube) could easily be produced with a tabletop device. The problem would likely be creating adequate beam density, which would likely be orders of magnitude more diffuse than the beam found in the LHC.

There is a problem with this calculation, however, since (as explained here), the power from a particle beam is not deposited directly at the point of contact with the target as occurs with a laser. Instead, the beam is scattered and a large portion of the energy is deposited in a cone behind the target. Somewhat counter intuitively, the more powerful the beam, the more energy is scattered away to places behind the point of contact with the target. Therefore, it isn’t at all clear how well such a beam could cut things compared to a similarly-powered laser. Likely, one would need a beam with at least MeV power to do that.

Fortunately, once again cold war era history can enlighten us – take the case of graduate student Anatoli Bugorski, who has entered into the annals of history as the only person unfortunate enough to be exposed to a particle accelerator beam. While working at the U-70 Synchrotron in the USSR he was struct with the proton beam in his head and experienced a bright flash of light, but no pain. It isn’t clear what the power of the beam was at that time, since we don’t know if he was hit by the LINAC injector (which had a power of 100 MeV) or the main synchrotron beam (which had a power of 70 GeV). I suspect it is more likely he was hit by the former since its harder to conceive he would be allowed in the main synchrotron while the beam was on, even with the lax security controls the USSR was famous for. The dose of ionizing radiation that Burgoski received was astronomical and normally would be fatal, but apparently since it was confined to a small part of his head he survived. During the first day after the incident he experienced severe swelling on the left side of his head. Later medical examination found that the beam literally burned a hole straight through his brain tissue. The left half of his face was paralyzed, due to the destruction of nerves and he lost most of his hearing in his left ear. Despite all of this, his mental function remained intact and he managed to finish his PhD, a resounding testament to graduate student tenacity. Soviet officials (and likely some profesors) forbade him to speak of the incident and it remained largely unknown for ten years. Ironically, later in life he became a “poster boy for Soviet and Russian radiation medicine”.

I think what the case of Anatoli Burgorski demonstrates is that, while the beam was able to cut through his nerve tissue, it was not powerful enough to kill him. Likely a large portion of the beam energy passed directly through him or was scattered in the “cone” mentioned before, which probably had a very small angle.

While I agree with Carlson that Tesla’s dream of stopping a million soldiers in their tracks is impractical due simply to the enormous amount power required, one must conclude that the general idea of particle beam weaponry is sound. The problem with realizing such a weapon is one of economics. The beam that struct Anatoli Burgorski required an accelerator complex that filled an entire building, hardly a weapon which is practical on the battlefield when a simple bullet can inflict more damage. While it is true that the most powerful particle accelerator in the world (the LHC) has considerable destructive power (the total beam energy is equivalent to a high speed locomotive), the facility cost ~$5 billion to build and requires $1 billion annually to run. It is also very hard to steer such powerful beams, requiring very high magnetic fields. Aiming such a beam would require many tons of superconducting magnets. The difficulty in steering a high energy beam is part of the reason why the radius of curvature of the beamline is so large (a radius of 2.5 miles at the LHC). Additionally, using a smaller radius of curvature causes more x-ray radiation to be produced (“synchrotron radiation”), which is harmful to humans and causes a large loss in beam energy. Clearly there are fairly strict physical constraints dictating that particle accelerators have to take up a large amount of space. There are surely many additional engineering reasons why particle accelerators are built with long beamlines (for instance, one can use more accelerating magnets, each of which are of rather limited power, and the time it takes for the beam to traverse the circumfrance of the tube is longer, which probably makes it easier to control.

Despite these difficulties, the idea of a neutral beam weapon was deemed potentially useful in at least one application – to destroy enemy satellites (as tested in the SDI BEAR project). However, the fact that the BEAR project only flew once and that SDI focused largely on lasers indicates that they were deemed more practical. In the end, it seems that the Department of Defense (and Navy) have settled on the laser as a more economical (and much lighter weight) alternative. Laser based weapons systems have recently been demonstrated on planes and ships.