Our Nature Communications paper – ice-like phonons in liquid water

Our paper, “The hydrogen-bond network of water supports propagating optical phonon-like modes” was published on January 4th in Nature Communications (full open access pdf). A press release about our work has been issued by the Stony Brook Newsroom and picked up by news aggregator Phys.org.

Our work shows that propagating vibrations or phonons can exist in water, just as in ice. The work analyzes both experimental data and the results of extensive molecular dynamics simulations performed with a rigid model (TIP4P/eps), a flexible model (TIP4P/2005f), and an ab-initio based polarizable model (TTM3F). Many of these simulations were performed on the new supercomputing cluster at Stony Brook’s Institute for Advanced Computational Science.

Liquid-state phonons

Phonons are usually considered to be solely a solid-state phenomena. In liquids, atoms or molecules are disordered and diffuse around, and there is no underlying order or crystal structure, so naively liquids should not be able to support coherent phonons. Water is special, however, because it contains a hydrogen bond network. We argue phonons can propagate through this H-bond network, just as they propagate through the H-bond network of ice.

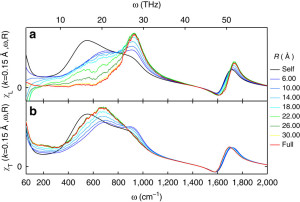

Unlike in ice, however, hydrogen bonds in water are constantly being broken and reformed, so the phonons only last for at most one trillionth of a second (1 ps). However, over this short time we show they can travel over surprisingly long distances of 2+ nanometers. We verify this range of propagation by breaking the transverse and longitudinal dielectric spectra into distance-dependent components:

To make this plot we considered spheres of various sizes around each molecule and analyzed the spectra using those spheres. When the radius of the sphere (R) is zero, then you are only considering single molecules separately and not considering how the dipole moments of different molecules add together. When you start increasing R, then you start considering adding together the dipole moments of molecules within a sphere around each molecule. Molecules that have dipole moments pointing in the same direction are said to be positively correlated and such correlation increases the dielectric response. Molecules that point in opposite directions are anti-correlated and decrease the response. At some far enough distance, the molecules become uncorrelated. When R is larger than that distance, the spectra no longer changes. The largest R accesible in our 4 nm box would be along the diagonal, which is R = 3.46. Surprisingly, in the librational band (400-1000 1/cm), the spectra does not stop changing until R is greater than 2-3 nanometers. To put that in perspective, a 2 nanometer sphere contains over 1100 molecules! The picture we arrive at is that of an extended quasi-tetrahedral (ice-like) hydrogen bond network that exists on picosecond timescales and allows for phonons to propagate through it.

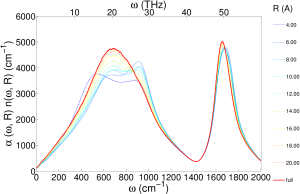

I also did a distance decomposed infrared spectra (unpublished), which shows the essentially the same information as the transverse dielectric susceptibility:

We focused specifically on optical phonons, which correspond to charge density waves that can interact with electromagnetic waves. In the case of ice, optical phonons cause well documented peaks in infrared and polarized Raman spectra. Similar absorption peaks are also found in the infrared and depolarized Raman spectra of liquid water.

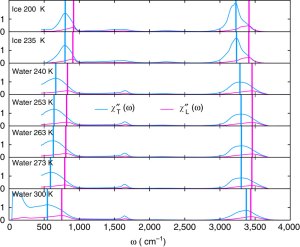

By comparing the experimental Raman, dielectric, and infrared spectra we show that peaks the librational and OH-stretch parts of the Raman & infrared spectra correspond to two different types of phonons, longitudinal and transverse. We identify longitudinal modes by looking a the longitudinal dielectric susceptibility.

The shifting of the position of the longitudinal and transverse peaks with temperature can be related to important structural changes in the hydrogen bond network, providing a new window into how water’s structure changes with temperature.

Relation to previous work

Our work builds on previous work on the nonlocal (k-dependent) susceptibility of water. More importantly, though, our findings challenge older ideas about water’s dynamics that characterized spectral peaks being due to the vibrational motions of at most a few molecules. In particular we reject previous interpretations of the librational band in Raman and IR spectra that assigned the three librational peaks to the librational motions of single molecules. Similarly, attempts to split the OH-stretching band cleanly into peaks from 2-Hbonded, 3-Hbonded, and 4H-bonded molecules are also called into question.

There is obviously some merit in understanding the spectra of bulk water by first studying the spectra of clusters of increasing size (Saykally, 2001). Under this approach it is usually implicitly assumed that when large clusters start to mimic the response of bulk water the size of such clusters indicates the spatial extent of vibrational excitations in the bulk. This is a questionable assumption. In some cases, particular clusters have been singled out as being particularly relevant to bulk water dynamics, in particular the cyclic pentamer (Bosma 1993). Our work contradicts the view that dynamics are confined to small clusters such as pentamers.

Relevance to the water structure debate

(see my post An introduction to the water structure problem )

We hope that our work can provide a new experimental window into water structure though the analysis of LO-TO splitting in the dielectric susceptibilities, as derived from experimental complex index of refraction data (n and k). From solid state physics theory it is understood that LO-TO splitting arises from long-range Coulomb or dipole-dipole interactions. In crystals, very long wavelength longitudinal optical phonons create a macroscopic electric field which increases their frequency relative to their transverse counterparts. Furthermore, as we discuss in our work, the degree of LO-TO splitting can in principle be related to structure. Intriguingly, we find an unexpected increase in the LO-TO splitting of the librational modes as temperature is increased.

Further implications

In biophysics, the results indicate that a new class of water-mediated protein-protein interactions may be possible. Recent work has shown dynamical coupling between proteins and surrounding water molecules (Ebbinghaus 2007), but the physical extent of this coupling is not very well understood. Currently this coupling is only being studied at low frequencies (< 33 cm 1/cm) (<1 THz), but our work indicates such coupling could also exist at much higher frequencies.

Additionally, by comparing several different simulation techniques, the we find that the non-polarizable water models fail to capture the optical phonon-like modes at the OH-stretch frequency. This compliments our previous work where we showed other ways that polarizable models are more accurate than the more often used non-polarizable models.

Note: this largely a cross-post from a piece I wrote on the MVFS group blog.