Geoffrey Hinton on what's wrong with CNNs

I am going to be posting some loose notes on different biologically-inspired machine learning lectures. In this note I summarize a talk given in 2014 by Geoffrey Hinton where he discusses some shortcomings of convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Convo nets have been remarkably successful. The current deep learning boom can be traced to a 2012 paper by Krizhevsky, Sutskever, and Hinton called ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Networks which demonstrated for the first time how a deep CNN could vastly outperform other methods at image classification.

According to Hinton, it is actually unfortunate that CNNs work so well, because they have serious shortcomings which he believes “will be hard to get rid of”. Recently, Hinton expressed deep suspicion about backpropation, saying that he believes it is a very inefficient way of learning, in that it requires a lot of data. In this lecture, Hinton points out some other issues with CNNs - poor translational invariance and lack of information about orientation (or more generally what he calls “pose”). Pose information refers to 3D orientation relative to the viewer but also lighting and color. CNNs are known to have trouble when objects are rotated or when lighting conditions are changed.

Convolutional networks use multiple layers of feature detectors. Each feature detector is local, so feature detectors are repeated across space. Pooling gives some translational invariance in much deeper layers, but only in a crude way. According to Hinton, the psychology of shape perception suggests that the human brain achieves translational invariance in a much better way. Hinton doesn’t discuss this, but we know that, roughly speaking, the brain has two separate pathways, a “what” pathway and a “where” pathway (see the “two-streams hypothesis”). Neurons in the “what” pathway respond to a particular type of stimulus regardless of where it is in the visual field. Neurons in the “where” pathway are responsible for encoding where things are. As a side note, it is hypothesized that the “where” pathway has a lower resolution then the “what” pathway.

The important thing to recognize here about the “what” pathway is that it doesn’t know where objects are without the “where” pathway telling it. If a person’s “where” pathway is damaged, they can tell if an object is present, but can’t keep track of where it is in the visual field and where it is in relation to other objects. This leads to simultanagnosia, a rare neurological condition where patients can only perceive one object at a time.

We know that edge detectors in the first layer of the visual cortex (V1) do not have translational invariance – each detector only detects things in a small visual field. The same is true in CNNs. The difference between the brain and a CNN occurs in the higher levels. Hinton posits that the brain has modules he calls “capsules” which are particularly good at handling different types of visual stimulus and encoding things like pose – for instance, there might be one for cars and another for faces. The brain must have a mechanism for “routing” low level visual information to what it believes is the best capsule for handling it. Note that if something analogous to capsules exist in the brain, they would lie in the “what” pathway. Of course, in such a system, “where” information is lost, but in most vision applications today, that is OK.

According to Hinton, CNNs do routing by pooling. Pooling was introduced to reduce redundancy of representation and reduce the number of parameters, recognizing that precise location is not important for object detection. However, according to Hinton, deep learning engineers haven’t really thought about routing specifically. Pooling does routing in a very crude way - for instance max pooling just picks the neuron with the highest activation, not the one that is most likely relevant to the task at hand.

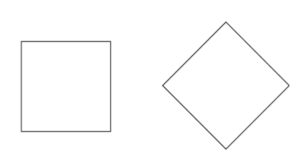

Another difference between CNNs and human vision is the human vision system appears to impose a rectangular coordinate frames on objects. Some simple examples found by the psychologist Irving Rock are as follows:

Very roughly speaking, the square and diamond look like very different shapes, because we represent them in rectangular coordinates. If they were in polar coordinates, they would differ by a single scalar angular phase factor and their numerical representations would be much similar. Likewise, it isn’t easy to tell what continent the shape on the right is, you have to try mentally rotating it. The fact the brain embeds things in a rectangular coordinate system means that linear translation is easy for the brain to handle but rotation is hard. Studies have found the mental rotation takes time proportionate to the amount of rotation required. CNNs cannot handle rotation at all - if they are trained on objects in one orientation, they will have trouble when the orientation is changed. According to Hinton, CNNs cannot do ‘handedness’ detection at all, even in principle. In other words, CNNs could never tell a left shoe from a right shoe, even if they were trained on both.

Taking the concept of a capsule further and speaking very hypothetically, Hinton proposes that capsules may be related to cortical minicolumns. Capsules may encode information such as orientation, scale, velocity, and color. Like neurons in the output layer of a CNN, a capsule outputs a probability of whether an entity is present, but additionally has pose metadata attached to it. This is very useful, because it can allow the brain to figure out if two objects, such as mouth and a nose, are subcomponents of an underlying object (a face). According to Hinton, the brain may have a fairly high dimensional “pose space”, with 20 or so dimensions. Hinton suggests it is easy to determine non-coincidental poses in high dimensions. Hinton says that computer vision should be like inverse graphics. So, while a graphics engine multiplies a rotation matrix times a vector to get the appearance of an object in a particular pose relative to the viewer, a vision system should take appearance and back out the matrix that gives that pose.

Toward the end of the lecture, Hinton shows a system that combines these concepts. Hinton’s system does about as well as a CNN in terms of classification accuracy. However, his system is much slower because it doesn’t not have the nice property of corresponding to a sequence of tensor operations (matrix multiplies) that CNNs have. Hintons code was written in Matlab and not optimized for speed, so future implementations, especially utilizing GPUs and other parallel hardware, could make them quite competitive with CNNs.