What would a science of AI look like?

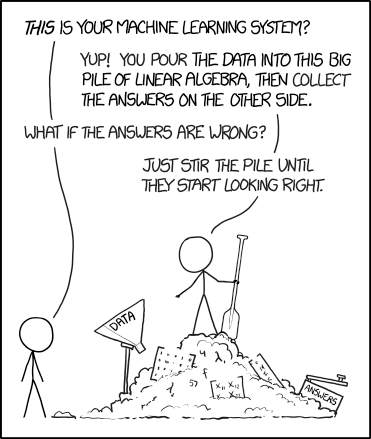

AI research today resembles prescientific fields such as alchemy or herbology. Like those other pre-scientific fields, AI research development relies on an evolutionary trial and error process guided by folk wisdom, intuition, and ad-hoc rules of thumb. Yan Lecun has defended this approach, noting that the first airplanes were built without a full understanding of aerodynamics. In a now-deleted Facebook post he noted that “the lens and the telescope preceded optics theory, the steam engine preceded thermodynamics, the airplane preceded flight aerodynamics, radio and data communication preceded information theory, the computer preceded computer science.” However, for the field of AI to reach its full maturity, as other areas of engineering have done, a scientific foundation is needed.

Even the best of today’s AI systems often fail in unexpected and embarrassing ways. Even top AI research outfits are not immune to this:

- 2015 - a deep learning system embedded in Google’s Photos service was found to be tagging African American people as gorillas. The quick-fix solution was to remove the category of gorillas. Three years later, WIRED magazine reported that the category was still missing, suggesting that the problem was not easy to solve.1

- 2017 - a much-lauded DeepMind deep reinforcement learning system for playing the Atari game Breakout2 was shown to fail if the paddle is moved 3% higher.3

- 2020 - a deep learning system for diagnosing retinopathy is developed by Google’s Verily Life Sciences and recieves much media fanfare after achieving human-level diagnostic ability in the lab. The same system then performed very poorly in field trials in Thailand due to poor lighting conditions, lower resolution images, and images which had been stitched together.4

If we do not understand a system in terms of general principles, we cannot predict how it will behave in new situations. Thus, having a science of AI is absolutely essential for AI Safety.

A science of AI would also speed progress towards more advanced AI, including AGI, just as advances in science have helped other areas of engineering. Currently the design of AI systems is done almost entirely through a process of trial and error combined with various “black art” heuristics. Just as the field of AI has gone through several “summers” (periods of rapid progress and excitement) and “winters” (periods of slower progress and disillusionment), the field has also gone through periods of more or less rigor. Unfortunately, a push for rigor in the 90s drove AI research away from neural networks because they are hard to understand mathematically compared to other techniques such as support vector machines (SVMs). Since SVMs had nice properties which were understood and could be proven, research on them was encouraged over neural nets, which were seen as untrustworthy black boxes. In light of this history we emphasize that undertaking a rigorous science of AI need not imply shutting down exploration and development of systems like neural nets which we poorly understand. This is especially true if we invest in new people – AI scientists – to do the job and leave the engineers to go about their business.

Rigorous scientific study of AI is currently not the norm

While the technological fruits of the current deep learning boom in AI have been numerous, the boom has also created many problems which have stymied scientific study of the systems being created. Firstly, the boom has led to many newcomers to the field, diluting the reviewer pool and weakening the rigor of peer review. As many new participants have entered the field, competition has skyrocketed, leading a push to publish new techniques and ideas as quickly as to avoid being ‘duped’ by competitors. A multitude of new conferences, typically with very low standards, has also arisen to support the increased number of people looking to publish their work. These factors have no doubt accelerated the technological progress of the field by allowing the rapid dissemination of new ideas. However, these factors have also made it difficult for those seeking to study AI scientifically to sort out the “wheat from the chafe”. We are drowning in a sea of low quality research.

Scientific understanding is not encouraged or incentivized either. Since the deep learning boom started most labs have become obsessively focused on benchmark chasing and achieving “wins” by showing that one’s proposed algorithms achieve “state of the art” performance on a benchmark compared to “baseline” techniques.5 The baseline techniques are sometimes chosen selectively to guarantee that the method being proposed wins. Comparisons are almost never done rigorously using full hyperparameter tuning of the models being compared and rigorous statistical comparisons are almost never done.5 AI researchers often perform tests in order to obtain confirmation of their ideas rather than focusing on falsification which is the key to the growth of scientific knowledge. Other problems are the use of obscurantist mathematics which are employed to lend an air of rigor and misleading papers which fail to properly distinguish speculative ideas and intuitions from established theory.6 There is also the overarching problem of lack of reproducibility which plagues not only AI but many other scientific fields as well.7 The result of all this is something which looks scientific but actually is not scientific at all.

What a true science of AI would look like

The field of AI can be traced back to the introduction of the artificial neural network in a paper by McCulloch and Pitts in 1943. The 1940s and 50s also saw the establishment of another field, cybernetics. The chief proponents of this field were Norbert Weiner (1894-1965) in the US and W. Ross Ashby (1903-1972) in the UK. The focus of cybernetics, according to Weiner, was “control and communication in the animal and the machine.” Weiner’s 1948 book Cybernetics firmly tied the field into existing theory in statistical mechanics and gestalt psychology. Many famous scientists and mathematicians from numerous different fields were active in cybernetics including Alan Turing, John von Neummann, Arturo Rosenblueth, Julian Bigelow, Warren McCulloch, and Walter Pitts. Each of these researchers took established theories and principles from their home fields and tied them into cybernetics.

Unfortunately the culture and approach of early cyberneticists has largely died out.5 Stuart Russell postulates the reason for this was that cybernetics was based on continuous mathematics (the calculus and matrix algebra familiar to physicists and engineers).5 Most AI researchers, then as today, did not have very advanced mathematical knowledge and preferred to work with discrete variables, symbols, and logic.

Any science of AI should be tied into existing science as much as possible so we can, as Isaac Newton said, “stand on the shoulders of giants”. Today’s theories about AI are typically quite removed from existing scientific knowledge and consist of a hodgepodge of ‘free floating’ mathematical ideas such as VC dimension and the minimal description length principle. Some popular theoretical ideas in AI, like the bias-variance trade-off taken from statistics, have been shown to not apply to deep learning.8

We think three existing fields can provide a foundation for the science of AI – physics, neuroscience, and evolutionary theory. Physicists have already employed mathematical methods from statistical mechanics to rigorously explain neural networks and the dynamics of neural network training (the interested reader can look up the Ising model, the replica method, and spin glass models). Neuroscientists have developed tentative theoretical frameworks for understanding brains, such as predictive processing, neural Darwinism, and the free-energy principle which tie into existing science. Finally, rich similarities between machine learning and evolution have been noted.8 The science of AI needs to be interdisciplinary, requiring transdisciplinary institutes and initiatives and incentivizing understanding over benchmark chasing.

Let’s not just invest in AI technology, let’s invest in a science of AI as well.

References

-

T. Simonite, “When it comes to gorillas, google photos remains blind”, January 11, 2018. WIRED. ↩

-

V. Mnih, et al. “Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning”, Nature 518 (7540) (2015) 529–533. ↩

-

K. Kansky et al. “Schema networks: Zero-shot transfer with a generative causal model of intuitive physics”, in: D. Precup, Y. W. Teh (Eds.), Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2017, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 6-11 August 2017, Vol. 70 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, PMLR, 2017, pp. 1809–1818 ↩

-

Beede, E.; et al. “A human-centered evaluation of a deep learning system deployed in clinics for the detection of diabetic retinopathy”, in: Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM, 2020 ↩

-

Russell, S. J.; Norvig, P.; Davis, E., “Artificial intelligence : a modern approach”. 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, 2010; p xviii, 1132 p. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Lipton, Z. C.; Steinhardt, J., “Troubling Trends in Machine Learning Scholarship”. ACM Queue 2019, 17 (1), 80. ↩

-

Barber, G., Artificial Intelligence Confronts a ‘Reproducibility’ Crisis. WIRED 09/16/2019, 2019. ↩

-

Hasson, U.; Nastase, S. A.; Goldstein, A., “Direct Fit to Nature: An Evolutionary Perspective on Biological and Artificial Neural Networks”. Neuron 2020, 105 (3), 416-434. ↩ ↩2